The Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies generous funding enabled me to conduct necessary research in Latvia for my dissertation, Surveillance’s Double-Edged Sword: Intelligence and Identities in the Soviet Union, 1918-1953. The Dissertation Grant Award funded my travel to and from Latvia, my room and board, as well as all transportation within Latvia. While in Riga, I worked every day at the Latvian State Historical Archives and the Latvian State Archives. The documents I found in both archives have proved vital to my project.

Centering on two major and interrelated themes in Soviet history—domestic intelligence and the creation of a socialist multiethnic union—my dissertation explains how and why the Soviets established the political police in the Soviet republics and argues that the political police served as both a destructive and a constructive force in the making of the Soviet Union. In addition to examining the functions of the political police within the Soviet system and Moscow’s management of this punitive organization, my project also takes a bottom-up approach and tells the story of the men and women who became part of the domestic intelligence service, and the challenges and successes these employees experienced as they engaged in this nation-building enterprise and policed their own family, friends, and neighbors. The result is a broader institutional and social history of the Soviet’s domestic intelligence service that considers the complex nature of local-level interests and conflicts while providing a more nuanced view of how the political police contributed to the creation of the Soviet empire.

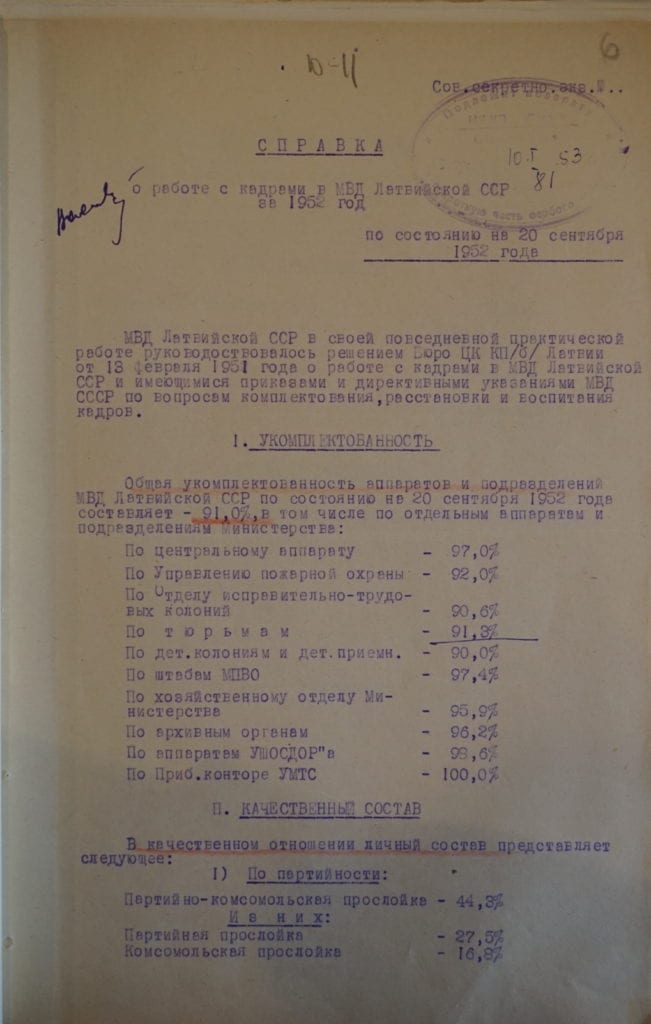

With the financial assistance from AABS I was able to read official communiqués, correspondences, internal reports, newspaper articles, and personnel files related to the creation of the Soviet Union’s most punitive institution. These documents are only available in Latvia, and my project would not have been possible without access to them. For example, in one of my dissertation chapters, I examine the creation of political police schools in the republics and the training of political police officers, rank-and-file servicemembers, as well as the militsiia men and women. When I began to work in the Latvian archives I was hoping that I could discover why Moscow decided to open up an inter-regional, political police training school in Latvia. However, the documents I had the opportunity to review enabled me to tell a more complete story about life in the Latvian training school. Using primarily internal school documents and correspondence with the Party leadership in Moscow I am able to explain the student application process while also contributing to our knowledge of the career tracks open to the student cadets and how their course load varied depending upon their track. I also found information about student behavioral issues the school administrators confronted as well as the challenges the administrators faced in adhering to Moscow’s dictates about how the school should operate. Historians have not yet written with this level of detail on the day-to-day operations of the training schools, and my project fills this gap in our knowledge by explaining how Moscow attempted to inculcate the next generation of Chekists at the schools.

With the financial assistance from AABS I was able to read official communiqués, correspondences, internal reports, newspaper articles, and personnel files related to the creation of the Soviet Union’s most punitive institution. These documents are only available in Latvia, and my project would not have been possible without access to them.

In addition to the information I found on training the political police, the most valuable documents for my project I found were the personnel files of the political police employees and reports on their behavior. These personnel files provide insight into the demographics of the officers and rank-and-file service members. In the manner of a prosopography, my dissertation follows the lives and careers of several political police employees through their recruitment, training, and daily tasks to better understand how and why ordinary citizens in Latvia became active participants in the Soviet project. Understanding who these low and mid-ranking servicemen were gives texture to an institution that to date has largely been examined only at the highest political levels and typically with a Moscow-centric view.

Moreover, the behavioral reports I accessed also increase our understanding of the challenges the Latvian Communist Party and political police leadership faced in controlling the employees of the internal and state security services. I discovered, surprisingly, that while the Latvian Party leadership was concerned with controlling the political police employees, they were also fixated on how the local population viewed the political police. The leadership remained preoccupied with maintaining a level of professionalism in the political police, even as the officers drank to excess, abused their positions, and engaged in non-sanctioned activities. From the sources I found I am able to make the case that Moscow did not have complete control over the regional political police departments as is typically depicted, but rather the employees and local circumstances ultimately impacted how the political police were able to execute the centrally dictated policies.

In addition to the valuable archival research I completed, I was also able to network with scholars in Latvia who share similar research interests. These connections have proven invaluable for both my current project and my future professional plans. I have spent the last

year writing my dissertation with the plan of finishing in 2021. My hope is that I will turn my dissertation into a book manuscript. I deeply appreciate the support that AABS provided me, which has helped me to bring my project to life.

Alexandra Sukalo

Recipient of 2019–2020 AABS Dissertation Grant Award