My new project is a history of tango in interwar Eastern Europe and Russia. At the heart of this history is Riga’s cosmopolitan community of musicians, performers, and poets, bohemians from across Europe and escapees from the Russian Revolution. Thanks to the support of the Research Grant for Emerging Scholars from the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies, I spent the summer of 2019 working at the Latvian State Historical Archive in Riga. On an earlier trip, I had surveyed the archive’s holdings, identified the relevant collections, and begun working with materials of the musicians’ association/professional union. I had started reading the protocols of the union’s meetings and musicians’ biographical questionnaires. Musicians included in these questionnaires information on musical education, language and ethnicity, places of employment, and the circuitous routes by which they had arrived in Riga. These applications allow me to create a collective biography of Riga’s musicians and to map Riga’s night life (the questionnaires provide addresses of cafes, restaurants, movie theaters, and resorts along the Baltic coast).

Eleonory Gilburd. © Eleonory Gilburd, 2020.

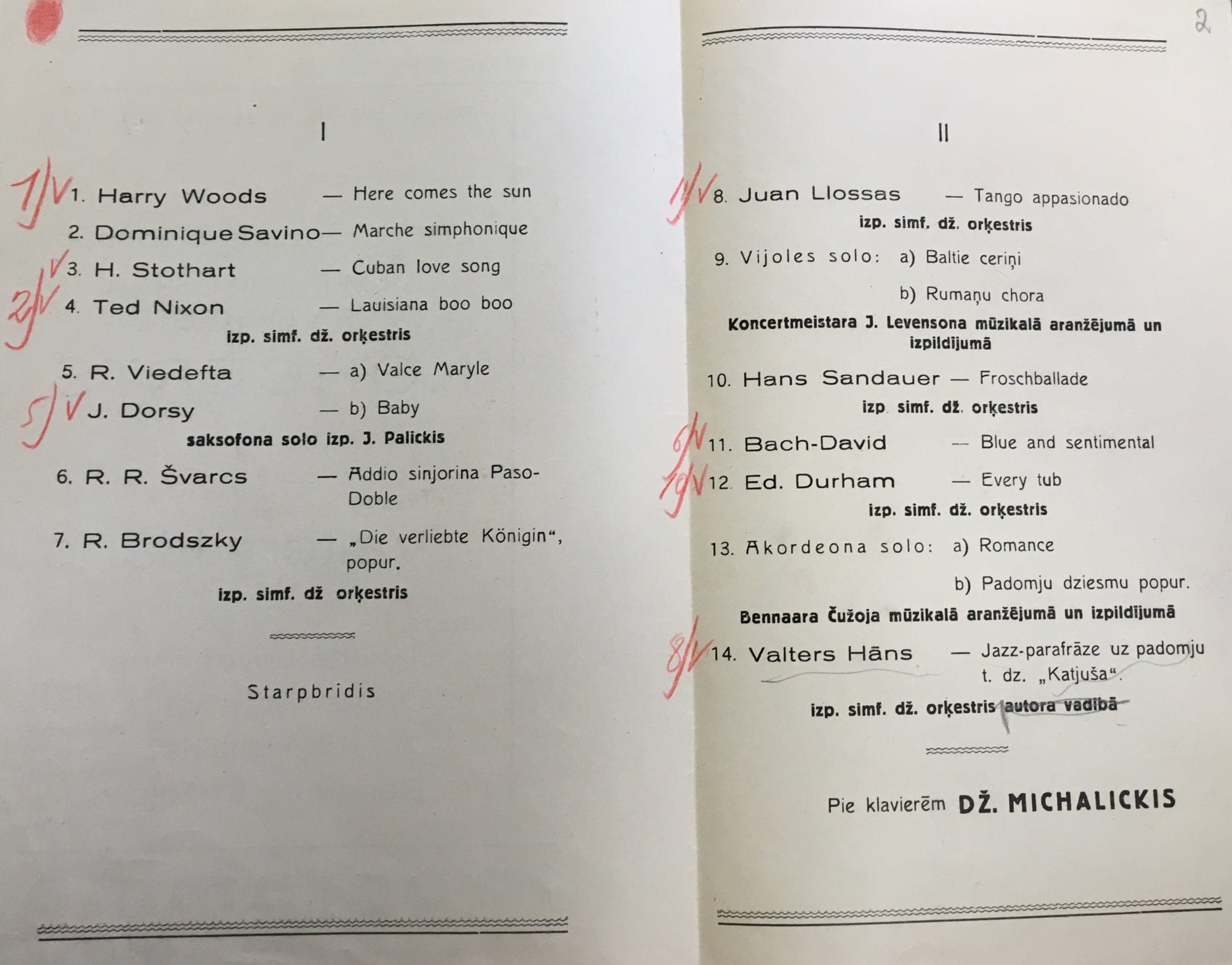

In summer 2019, I finished gathering these questionnaires and expanded my research to other documents in the collection of the musicians’ union, to other musical organizations, and to the records of the film industry. One of the richest sources was fond 6202, with materials covering the late 1930s and with extensive documentation on the Soviet takeover of musical institutions. Concert programs and band repertories that I found in this fond reveal what people going to café Opera, turning on the radio, stopping by the lobby of hotel “Riga,” or attending an evening of Valters Hāns’ Symphonic Jazz Orchestra actually heard. Every repertory included a tango – Juan Llossas’ “Appassionato tango” was a staple of Symphonic Jazz’s programs, for example – or broadly defined “dance music,” mainly of American and German provenance. While the repertory lists are fragmentary (they do not cover the entire interwar period, nor the entire spectrum of performance venues), they nonetheless offer a remarkable level of specificity and concreteness.

They also allow me to trace how Riga’s soundscapes changed in 1940. Russian songs often had been part of repertories in the interwar years: Russian patrons frequented central restaurants, and Russian and Russian-speaking Jewish musicians were a conspicuous presence in popular bands. But songs from Soviet films and Soviet marches appeared in Latvian soundscapes almost immediately following occupation. Bands played at signature Soviet cultural events, such as a screening of Battleship Potemkin.

Meanwhile, official correspondence between musicians and the Administration for the Arts (of the Council of People’s Commissars) demonstrates the specific ways in which Soviet practices and sympathizers were grafted onto existing institutions. The documents also show redistribution of space and property as the Soviet authorities disbanded corporations and associations. Accommodating to the new regime, the union petitioned for apartments and furniture for itself and employment opportunities for its members. I was delighted to find these documents. One of my book’s running themes is the fate of cultural infrastructure and relationships established under the old regime in new, revolutionary times and in periods of transition from private to state enterprise. And these materials beautifully complement my findings from St. Petersburg’s archives on Russian movie and variété theaters, cafes, and restaurants in the 1920s – in two moments of transitions, from imperial to revolutionary regimes, and from the New Economic Policy of limited private enterprise to Stalinism.

One of my book’s running themes is the fate of cultural infrastructure and relationships established under the old regime in new, revolutionary times and in periods of transition from private to state enterprise.

Files in fond 6202 also show how musicians interacted with entertainment venues, that is, their employers, and with political authorities both before and after the Soviet occupation. A cache of letters from private music teachers in response to an appeal in the newspaper Labor gazette (from 1940) shows how musicians tried to reconstitute themselves under the new regime. They often gave piano, violin, or voice lessons on the side, in addition to working in Riga’s entertainment venues. And in the first months of occupation, those who had remained – I also found lists of musicians who had emigrated to Germany – had tried to refashion themselves for the new times. Some discounted socio-economic factors and instead wrote about their students’ great talent and admission to the conservatory; others spoke about poverty, low pay, lack of insurance and pensions, and the disappearance of students as Volksdeutsche families departed for Germany. And yet others went a step further, blaming the old association of musicians for failing to look after their material wellbeing. All of them hoped for jobs and recognition under the Soviets. These letters show confusion about Soviet terminology and the boundaries of the permissible: many had been educated in imperial St. Petersburg, which they now christened Leningrad even as the described the 1890s and 1910s; many had escaped the Russian Revolution and arrived in Riga after circling around Europe – only to find themselves face to face with the Soviet regime. One striking characteristic these musicians shared was their international experiences: they all had either been educated or lived and performed in Berlin and Dresden, Vienna and Milan, Moscow and St. Petersburg. All led peripatetic lives. Enumerated as a matter of fact, the dates of their departures and arrivals, 1918, 1921, 1933, tell the drama of the first quarter of the 20th century. Even as these letter writers searched for a language in which to address the new Soviet institutions and relied on formulas, their letters offer an uncommon view into their private worlds.

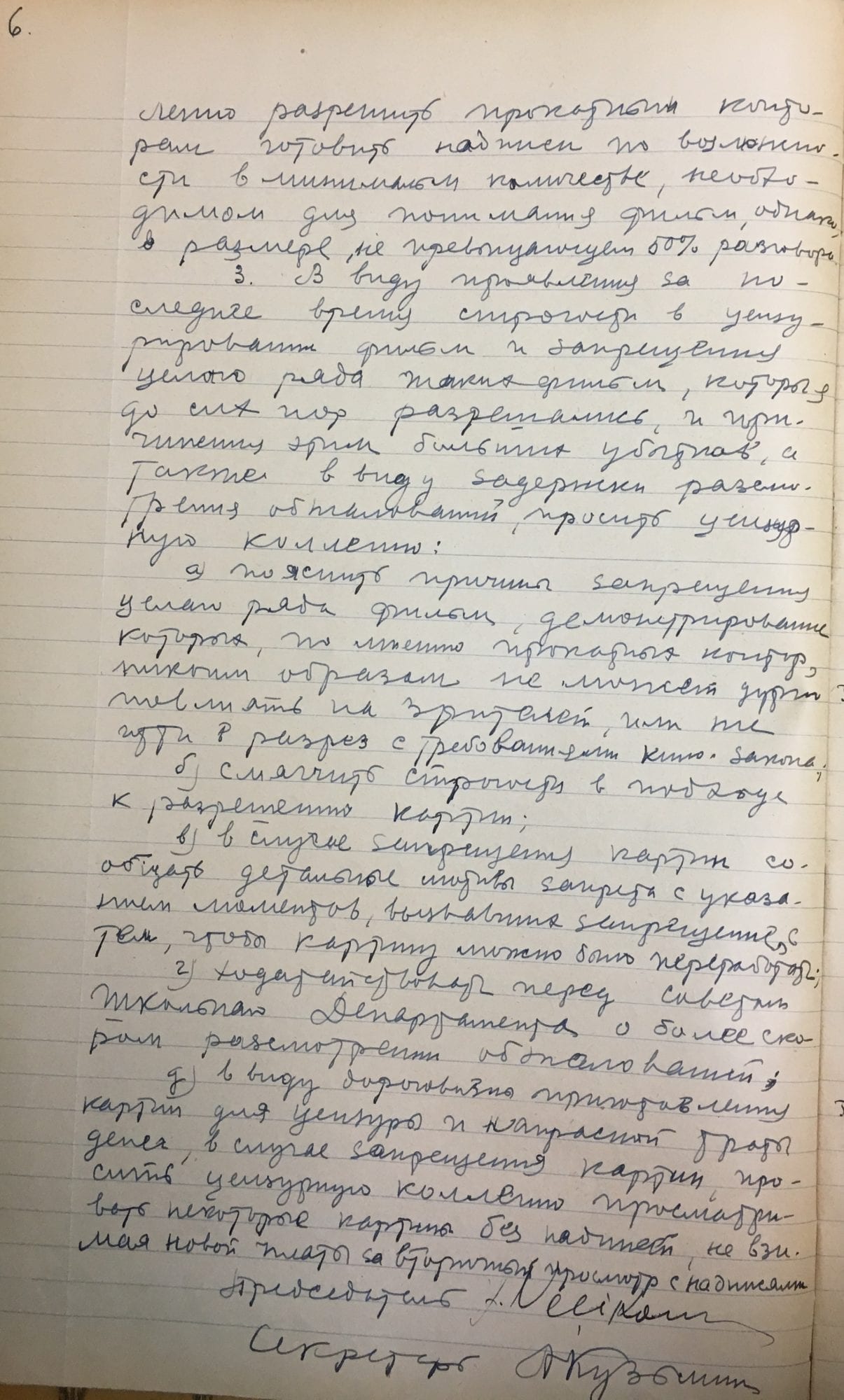

Movie theaters were one of the key entertainment venues employing musicians and popularizing tangos. Musicians played the piano to accompany silent film screenings; sound brought music to the screen itself. And before or after film screenings, bands played popular melodies in theater foyers – in special divertissement programs that included dancing, skits, and other acts. That is why on this research trip I turned to archival collections concerning movie theaters, their owners and employees. I found fond 2358, the association of owners of Latvian movie-theaters and film distributors, especially valuable. This fond contains minutes of the association’s meetings and correspondence with the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Finance, the department of self-administration at the Ministry of International Affairs, and Riga’s prefecture and municipal council. Three broad themes emerge from these materials: import of foreign films, censorship, and taxes on sound films or films accompanied by fotoplayer music. These themes were interrelated, at least in the early 1930s, a period for which documentation is systematic. Movie-theater owners fought rising taxes on divertissement, on sound, and on entertainments in general; they fought doggedly, drawing on legal advice, petitioning, sending representative to municipal assemblies, and threatening theater closures – they were prepared to paralyze Riga’s night life. It appears that theater owners understood the tax on entertainments (which vacillated between 30 and 50%) not only as an economic measure, but also as an attempt to control divertissements. The tax emerged as part of a new legislation that also banned viewers under 18 years old from the movies; and film entrepreneurs deliberated on the tax in the same line of thought as on censorship and importation restrictions. Or, perhaps, they saw attempts by the censorship collegium (at the Ministry of Education) to regulate morality as similar to taxation, because both had unwelcome economic consequences: entrepreneurs bemoaned the profits they lost because of more stringent censorship. At this time, censorship was technologically inept – audiences would see a black screen in places where cuts had been made and grow restless and disruptive, their ire falling on theater owners.

A page from the minutes of a meeting of the association of owners of Latvian movie-theaters and film distribution companies, December 12, 1933; the discussion concerns film censorship. Latvian State Historical Archives F. 2358 s. 1 i. 4, p. 6.

The censorship collegium also made decisions on film import with a view to what pictures were appropriate for “local conditions,” and no film could be shown without its approval. In the 1930s, Riga was the center of film distribution for the entire Baltic region: all foreign films first passed through Riga, whence distributors transported them for screenings across Estonia and Lithuania. Restrictions on importation left the treasury bereft of import tariffs and entrepreneurs bereft of profits. These archival records suggest that sound pictures and the music that surrounded film screenings seemed suspect to a censor’s eye. The documents provide a crucial backstage for understanding the relationship among musicians, film entrepreneurs, and moral authorities (censors, pedagogues). I yet have to figure out what was so disturbing about the music in foyers and divertissement more generally, what films were arrested at the point of import, and what parts of what films were excised by censors. My interest in censorship has been spurred by the frequency with which it appears in archival records, whether in documents about cinema, music, or even about celebrations and dancing that various associations staged.

Pages from a concert program of the Jazz Symphonic Orchestra from September 30, 1940. Latvian State Historical Archives F. 6202 s. 1 i. 50 p. 1 over–2.

Finally, I want to mention a more universal source – protocols of meetings of various associations. The unions of musicians, theater owners, and cinema workers all kept minutes of their meetings. The unions regulated employment for musicians and film mechanics, pressured restaurant and theater owners for higher pay, and guarded the cultural labor market against foreigners – already in the 1920s, the musicians’ association berated venues that hired foreign performers and often coerced orchestras and restaurants to employ only Latvian citizens. The musicians’ association had been founded, according to its statute, to promote Latvian music; but this aesthetic and national project had economic ramifications, as the society monopolized contracts between musicians and business owners. These sources open up another perspective on cultural life in Riga: the routine economic rationale and small, mundane acts that spun the wheels of the entertainment industry. The minutes of meetings hardly mention aesthetic or political concerns, but expose the pragmatic and contingent factors behind cultural offerings – factors that do not get sufficient treatment in scholarship.

On my next archival trip to Riga, I intend to pursue several leads from this research. In the meantime, the research I conducted in summer 2019 has given me such a treasure trove of material that I can starting drafting the Riga chapters of my book.

On my next archival trip to Riga, I intend to pursue several leads from this research. I appreciate having a list of musicians for dozens of popular bands performing in movie theaters, on the radio, and at restaurants: I plan to examine several figures more closely. One such figure is virtuoso violinist Jēkabs Levensons, who played in prominent venues; was highly regarded in the Russian-language press; toured the Baltic Sea coast, performing tangos and foxtrots for middle-class vocationers in summer months; and, as a member of the Symphonic Jazz Orchestra, performed at Soviet film screenings.

In the meantime, the research I conducted in summer 2019 has given me such a treasure trove of material that I can starting drafting the Riga chapters of my book. In 2021-2022, I am eligible for a sabbatical, and I will begin writing on the basis of this research. I am deeply grateful to the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies for supporting my work and giving me this invaluable opportunity to spend summer 2019 immersed in the archives.

Eleonory Gilburd

Recipient of AABS 2019–2020 Research Grant for Emerging Scholars

Other Grants and Fellowships News

Vanished Lands: Book Publication Subvention Report by Laima Vincė Sruoginis

The Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS) is pleased to recognized the successful conclusion of a Book Publication Subvention Grant awarded to Peter Lang Publishers for publishing the book Vanished Lands: Memory and Postmemory in North American...

Elīna Vikmane Birnitis Fellowship Report on Advancing Cybermuseology

AABS is pleased to recognize Elīna Vikmane for the completion of her dissertation "Advancing Cybermuseology: Diffusion of digital innovation in Latvia’s museum sector," for which she received the 2022–2023 Aina Birnitis Dissertation-Completion Fellowship in the...

AABS 2024 Grant and Fellowship Applications Open

Call for Applications AABS 2024-2025 Grants and Fellowships Research Grants for Emerging Scholars The Aina Birnitis Dissertation-Completion Fellowship in the Humanities for Latvia Mudīte I. Zīlīte Saltups Fellowships Jānis Grundmanis Fellowships for...