AABS is pleased to congratulate Gary Uzonyi for the completion of his project “Baltification,” for which he received the AABS Emerging Scholars Grant.

©Gary Uzonyi, 2023

Dr. Gary Uzonyi earned his PhD from the University of Michigan in 2013. He is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. His research focuses on international cooperation around issues related to global security. His current project focuses on the changing landscape of Baltic security.

The Impact of an Award: Report from Gary Uzonyi

After the completion of his project, Gary Uzonyi submitted a reflection to AABS.

We thank him for his permission to publish his thoughts, which have been lightly edited.

The Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies generously funded my research on “Baltification” and the changing landscape of Baltic security. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are each members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Military alliances, such as NATO, promise to provide minor powers—like the Baltic States—security in return for their compliance with the broader foreign policy agendas of the agreement’s major powers. While arming may take time and be contingent on a country’s resources, alliances promise to provide a rapid increase in strength to a member who is targeted by an outside aggressor. Yet, the formalization of the alliance often goes further. As part of this tradeoff, the minor power countries also expect to receive combat, logistical, and professionalization training from the major powers. In exchange, the major powers expect them to re-organize their military structures and approaches to security. For Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania within NATO, this restructuring became known as the process of “Baltification” (see Jüri Luik’s 2002 discussion).

While Baltification was intended to better integrate the Baltic States’ militaries within the NATO structure, it largely siloed the region’s militaries as the larger alliance’s north-eastern bulwark against Russia. While the Baltic States routinely coordinated with one another through BALTBAT, BALTRON, BALTNET, and BALTDEFCOL, integration into the broader NATO-cooperative has been slower over the past two-plus decades. This project seeks to understand three questions. First, how has the two-plus decade process of Baltification shaped Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania’s approach to understanding security, training of personnel, and the role of the military? Second, how has tight Baltic cooperation influenced the process of NATO integration for these states? Third, how have the Baltic States balanced the demand for European security with the growing call for the humanitarian involvement of NATO and the European Union (EU)?

To understand the changing landscape of Baltic security alongside NATO’s siloing of the region, I conducted interviews of key politicians and the head or rector of each country’s military academia, along with the staff members of BALTDEFCOL to explore how these key figures understand the cooperative process at each of the Baltic, European, and NATO levels. These perceptions are crucial for understanding how the Baltic States experience the “security dilemma” within their overlapping organizational structure and between the major powers that operate inside and outside these alliances. I was successful in interviewing 8 Estonian, 8 Latvian, and 1 Lithuanian MPs, as well as the Dean of BALTDEFCOL and the rectors of both the Latvian and Lithuanian military academies. In this report, I will discuss my interviews of the politicians before turning to my discussions with the rector and staff of the military academies.

I asked the members of parliament a series of questions around three key areas. The first area was the level of Baltic military cooperation: what is working, what is not working, how has the cooperative experience been for their country specifically? From these interviews, two themes emerged that were crucial to the discussions that followed. First, while the Baltic States are often treated homogenously by their NATO allies (the siloing mentioned above), each state is independent and has its own history, goals, and ways of thinking about the military and security. Second, despite this independence, there have been three pivotal moments that each of the countries have shared that must demarcate different periods of cooperation. The first moment was independence from the Soviet Union in mid-1990. Following independence, and having limited resources, the Baltic States actively attempted to cooperate as a region to aggregated their military resources. The second moment was NATO membership for each of the countries in 2004. Following NATO membership, any discussion of Baltic cooperation is one of cooperation in NATO, rather than in the region. The third moment began with Russia’s hybrid attacks against Ukraine in 2014. Since then, the Baltic States have once again focused on Baltic regional security and more joint military planning, as their larger NATO partners have moved more slowly in planning for the region.

Three overall patterns emerged from this set of questions. First, military cooperation in the immediate post-Soviet phase was difficult due to those differences in military experience, resources, and emphases. On a 0 (very low) to 5 (very high) scale, the majority of respondents rated early military cooperation as a 2 or 3 despite the creation of BALTBAT, BALTRON, BALTNET, and BALTDEFCOL. Second, cooperation greatly changed when the states joined NATO. Now, regional cooperation was much less important and much less sought after. Some MPs noted that asking about Baltic cooperation during this period is misleading because all cooperation was funneled through NATO and the Baltic States no longer looked to one another. However, others noted that the Baltic States still cooperate as “one front” and possess a “single 3B (three Baltic states) position within NATO.” Third, Russia’s attacks on Ukraine have greatly changed cooperation. Now, the countries are working closely together on everything from procurement to operational planning because they understand that NATO’s plans are—should the war in Ukraine expand to the Baltic—to let the Russians overrun the region, have them exhaust their military, and then to counterattack Moscow. While this may lead to victory, it would be a devastating war for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. On the 0-5 scale, all MPs rated cooperation today either as a 4 or 5.

The second area of questions concerned the factors that help or hurt military cooperation: venue, issue linkage, domestic concerns, and/or international concerns. Two themes emerged here. First, NATO is the best venue for cooperation. Often, scholars argue that states will seek those venues that allow them the most autonomy over policy. For the Baltic States, though, the primary concern is territorial defense. NATO is superior to only intra-Baltic cooperation because it provides more and stronger allies. Here, the MPs routinely referenced American military strength. NATO is also superior to an EU-only defense program because (a) an EU program would require building parallel and redundant institutions and (b) would largely duplicate NATO but without American military strength. Thus, while the Baltic states would have more policy autonomy in either an intra-Baltic or EU focused security arrangement, they prefer the security of NATO. Second, while many scholars see connecting non-military issues to military issues as helping to strengthen cooperation (“issue linkage”), the MPs saw cooperation on these other issues as largely unrelated. The majority of MPs noted that deep cooperation on other issues is part of the Baltic States’ history, and has existed and continues outside and unrelated to NATO. That is, the majority of respondents see non-military cooperation as important but not directly tied to military cooperation.

The final area of questions examined the reasons for cooperation: security, material gain, prestige, diversity of strategic thinking. Two themes emerged from this set of questions, as well. First, the MPs noted territorial defense as the primary reason for military cooperation. Furthermore, each MP noted that the primary concern of each Baltic State has remained unchanged since 1990: Russia. Second, the MPs were divided in whether prestige of their country influenced security strategy. While some responded that gaining prestige had no role in their decision calculus, others noted that all countries—including their own—want to be seen as good and important members of the international community. However, the MPs agreed that prestige played a much smaller role than guaranteeing their territorial sovereignty. Furthermore, on the issue of peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, the majority of MPs responded that their desire was to participate in NATO (not UN) operations because such engagement helped demonstrate that their country was a helpful member to the alliance. This is important because helping the alliance meant that the alliance would be willing to help in times of need.

Many of the MPs saw BALTDEFCOL as an important institution that helps promote Baltic military cooperation, even with the primary shift to NATO. At the Baltic Defence College (BALTDEFCOL or “BDC”), I interviewed the college’s Dean and lead researcher. These interviews elaborated on the discussion I had with the MPs. Specifically, while the BDC was formed in the 1990s, its aim was to help the Baltic States gain NATO membership. Now, its curriculum is crafted to meet NATO standards. However, the BDC still plays an important role in building cooperation. It helps build cooperation by being the bridge between the military and political—it helps lubricate future cooperation by helping those military officers selected by their countries to attend the school get to know each other, the ways in which the NATO system works, and how each country’s political and military actors think. That is, the focus is not on military training per se, but why the system works the way that it does.

A given country’s military academy functions quite differently, yet plays a similar role. Since each country is a NATO member, its military academy trains its aspiring officers along NATO criteria, but with an eye towards the individual country’s emphases and strategies. The harmony between the academies and NATO standards is driven by the Ministry of Defence (MOD), which lays out the instructional plan for its country. These set standards help cooperation at its most basic military level—interoperability. However, through their academic wings, the academies offer more to the overall system of cooperation. While the academic side of the academy is independent of the military science functions, the students are the same. Thus, the academies emphasize Baltic history and politics. They also host exchange students and emphasize an understanding of “the other”. The academies also cooperate on curriculum development. Overall, then, the military academies, despite their various approaches, tend to contribute to cooperation by providing settings that help members of the military reduce their uncertainty about the motives and systems within the region.

Returning to my original three questions, I now have an outline of an answer to each. First, how has the two-plus decade process of Baltification shaped Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania’s approach to understanding security, training of personnel, and the role of the military? Intra-Baltic military cooperation was emphasized in the immediate post-independence phase, but NATO membership had always been the goal. This goal, and eventually gaining NATO membership, has diminished sole intra-regional cooperation in favor of broader NATO cooperation. While the Baltic States are often siloed within NATO, the alliance’s standards have marked a clear path forward for these countries. Second, how has tight Baltic cooperation influenced the process of NATO integration for these states? The answer to this question flows from that of the first. Since NATO membership was the goal, the Baltic States matched their military standards to those of the alliance even before achieving membership. This collective goal led to each country’s MOD harmonizing training from the academy level throughout each branch of their militaries. Third, how have the Baltic States balanced the demand for European security with the growing call for the humanitarian involvement of NATO and the European Union (EU)? The MPs stressed that NATO, rather than EU, involvement is key to their security. Peacekeeping, and other humanitarian missions, are not a balancing act with solidifying their territorial defense. Instead, participating in these operations increases the likelihood that NATO will come to their defense, should it be needed.

Despite these encouraging first steps towards building a better understanding of Baltic military cooperation and collective security, there is still more work to do. Moving forward, there are more avenues to explore in the short run. First, I plan to continue conducting interviews of MPs and military academy staff. Second, I plan to team with academics at the BDC to conduct further research on the current security situation in the Baltic. As an initial step in this direction, we have begun a pilot survey to understand how citizens in eastern Estonia feel about the likelihood of NATO protection should Russian troops cross the border.

It is important to note that this report is a brief summary of the interviews conducted. The next step will be to elaborate on the questions and answers provided in manuscripts addressing these discussions alongside the broader academic literature on military cooperation.

– Gary Uzonyi, 2023

Gary Uzonyi

What is the Emerging Scholars Grant?

The Research Grant for Emerging Scholars is an award for up to $6,000, to be used for travel, duplication, materials, equipment, or other needs as specified. Proposals are evaluated according to the scholarly potential of the applicant and the quality and scholarly importance of the proposed work, especially to the development of Baltic Studies. Applicants must have received PhD no earlier than January 1, 2013. Applicants must be AABS members at the time of application.

The application deadline for academic year 2023-2024 is February 1, 2023. Applications will be evaluated by the AABS 2023–2024 Grants Committee consisting of AABS VP for Professional Development Dr. Kaarel Piirimäe, AABS President Dr. Dovilė Budrytė, and AABS Director-at-Large Dr. Daunis Auers. Award notifications will be made in April 2023.

Other Grants and Fellowships News

Vanished Lands: Book Publication Subvention Report by Laima Vincė Sruoginis

The Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS) is pleased to recognized the successful conclusion of a Book Publication Subvention Grant awarded to Peter Lang Publishers for publishing the book Vanished Lands: Memory and Postmemory in North American...

Elīna Vikmane Birnitis Fellowship Report on Advancing Cybermuseology

AABS is pleased to recognize Elīna Vikmane for the completion of her dissertation "Advancing Cybermuseology: Diffusion of digital innovation in Latvia’s museum sector," for which she received the 2022–2023 Aina Birnitis Dissertation-Completion Fellowship in the...

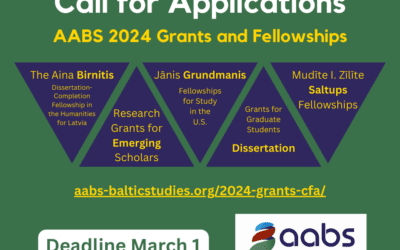

AABS 2024 Grant and Fellowship Applications Open

Call for Applications AABS 2024-2025 Grants and Fellowships Research Grants for Emerging Scholars The Aina Birnitis Dissertation-Completion Fellowship in the Humanities for Latvia Mudīte I. Zīlīte Saltups Fellowships Jānis Grundmanis Fellowships for...

Renew your membership or join for 2023 online or by mail.

Donate

Contribute to the Baltic Studies Fund (BSF) or AABS program expenses to ensure the future well-being of AABS.

Connect with AABS

Find AABS on the following networks

Newsletter

Lokal_Profil (CC BY-SA 2.5) | © 2022 The Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS) | A member of the American Council of Learned Societies